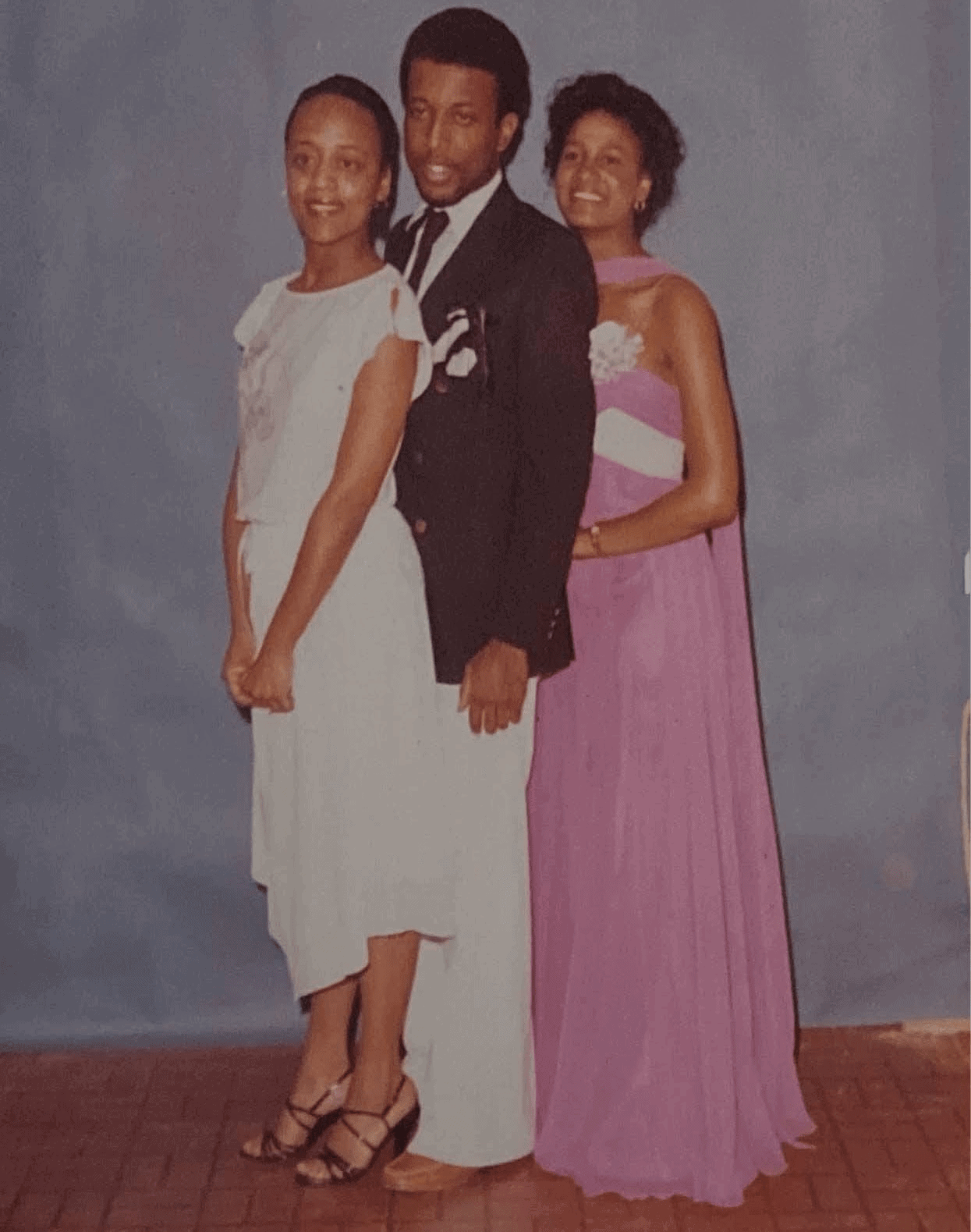

I often chuckle at a picture in my family home (which hangs in the elegant living room where no one ever sits) of my aunt’s high school prom. My 23-year-old uncle is standing in between my 25-year-old mom and my 17-year-old aunt as everyone grins from ear-to-ear. What are two grown ups doing at their little sister’s prom?

My aunt’s high school refused to have an integrated prom, so my aunt and her friends decided to throw a party just for Black students. Given racism and their limited budget, she asked her adult siblings, my uncle and mom, to chaperone the prom and both enthusiastically agreed. Whenever someone in my family gleefully tells this story, I always think about what an incredible act of resistance it is to find humor in something so dark. Daring to find humor, joy and even belonging in a society that was built to ignore your existence is bold.

My family home was often filled with Black joy. There were plenty of deep belly laughs to go around: from this often-retold prom story to the time I dressed up as Jimmy Carter, a peanut farmer from my home state of Georgia, even though I was deathly allergic to peanuts. I didn’t realize this at the time, but the laughter in my home was a form of Black resistance that is deeply embedded in my family — and which is essential to my vitality.

It’s an example of resistance that Black people have used for generations to create a sense of belonging and community and challenge oppressive systems that marginalize us. As Lawerence Levine described it: “The need to laugh at our enemies, our situation, ourselves is a common one but exists more urgently in those who exert the least power over their immediate environment.” By using humor, Black people find some form of collective power in places where we aren’t given any power.

I learned this strategy not just from my family but from the many segments of Black culture I absorbed as a kid. Occasionally, I find myself thinking about the offensive yet beautiful character known as George Jefferson of The Jeffersons, which I watched reruns of growing up. While there were many problematic and racist elements of that show, the premise was that a Black family used entrepreneurship to access wealth in the 1970s, entering into a white space all while still daring to be Black. I always think of the way George Jefferson would strut into the room with his ridiculous waddle and his loud, unfettered commentary about the old white people surrounding him in his “deluxe apartment in the sky.” These reruns taught me to have unfettered commentary about uppercrust white people as an adolescent — and that I could find humor in even the most uncomfortable situations where I felt like I didn’t belong because of the various identities I hold (mainly being Black and a woman).

You’re probably wondering, “What in Beyonce’s name does humor have to do with diversity, equity and inclusion work?” Let me ask you this: Have you ever gone to an organization’s website to look at their commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion and noticed that each and every single employee headshot looks like the football-headed Arnold of the critically acclaimed “Hey Arnold?” The gap between aspiration and reality feels comically obvious to those of us who have been at the margins of society. A half-hearted attempt at inclusivity comes across as some kind of “We are the World” advertisement.

But humor doesn’t just help me cope with the gap — it also helps me begin to chip away at the complexities of injustice: through humor, I can illuminate some of the structures and implicit biases that create inequitable outcomes in the workplace. For example, when an organization’s leaders wonder why they struggle to get “diverse” candidates but also have an employee referral program where all of their white employees just refer all of their white friends and business school classmates, I can’t help but laugh at this clear collective bias that manages to remain invisible to the organization. Sidenote: People can’t be “diverse” as individuals. Just say People of Color and call it a day. POC isn’t an offensive term. It just is.

Humor also puts people at ease and facilitates honesty in a way that we are traditionally not accustomed to in the workplace. Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) work is not easy. It can require me to lead folks through defensiveness and trauma all while being conscious of my own privileges and identities that inform how I approach the work. Humor facilitates trust. As someone who leads DEI work, I can admit to a client that there was a time in my life when I was obsessed with argyle because I thought it was a perfect way to subtly and fashionably assimilate with my white peers growing up. We can all objectively say that argyle is neither subtle nor fashionable. After making a joke, I can then be more serious and people will hear me better. I can say that I am on an ongoing journey to unlearn societal beliefs about my worth as a Black woman that were ingrained in me. Using humor to acknowledge my own shortcomings allows others to feel comfortable to do the same.

I will say that I have found it truly hard to laugh this past year. From the collective pandemic anxiety, to the invisibility of Breonna Taylor’s life and murder, to my own personal grief, I feel done laughing. Laughter has seemed like a luxury. As I write this, I am looking at the news of the Asian women murdered in my own hometown of Atlanta, an ugly act of violence that has been on the rise against Asians in the United States for the past year. This is absolutely not funny.

This tool that I’ve historically used to resist has been inaccessible to me when I’ve needed it the most. To be clear, I’m still objectively funny (can’t you tell?), but I am not personally enjoying humor – including my own – in the way I once did. Humor can’t wield the power to resist or even connect across differences in the way that it has for me previously if I don’t feel like I have any power over it. For a while, I blamed myself for losing my funny bone. But then I realized that the same system I am using humor to fight against is also ruining my life. How messed up is that?

I will need to rediscover the joy in humor to sustainably resist the systems that actively shape our inequitable society. I look forward to the day it fuels me to resist. In the meantime, I am resting, listening to my favorite Black comedians, watching Gen Z dance exclusively with their arms on TikTok, dreaming about Funions and recharging. I look forward to the day when I feel I have the power to use and dare to enjoy the tool I know best again.

KIERA VINSON

Consultant

She/Her/Hers

Contact Kiera: kiera@promise54.org